The

effect of the Spanish Peninsular war on the 19th century national

consciousness was in some ways similar to our own feelings about battles on the

Western Front during the First World War. Both were part of a much wider

conflict; both were extremely bloody; and both had a huge effect back in Britain.

And,

as always happens in war, stories emerged which caught the public imagination. One of these was the (true) story of the Maid of Saragossa. Readers of Georgette Heyer's The Spanish Bride will remember the scene when Juana intrepidly rides back to their previous lodgings to return a stolen Sevres bowl to its owner. 'Well done, Juana!' exclaims Colonel Barnard. 'You're a heroine. Why, the Maid of Saragossa is nothing to you!'

Wellington's HQ at Ciudad Rodrigo

I

was reminded of all this when I saw the Scottish artist David Wilkie’s paintings of the Peninsular

War in the Royal Collection at the Queen’s Gallery. I’d seen lots of

contemporary prints of the war but not proper oil paintings, so I was

interested to see these.

Wilkie

visited Madrid in 1827 and, inspired by stories of Spanish guerrilla resistance, painted

a series of pictures from the Spanish point of view. It is interesting that

Wilkie chose the Spanish as his subjects. Perhaps he had seen too many returned

British soldiers, wounded and out of work, begging on the streets for him to

want to glamorize them.

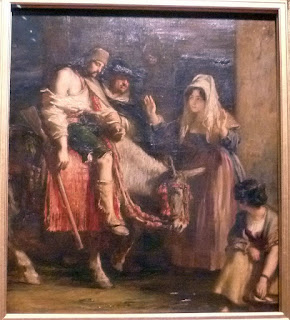

The Guerrilla’s Departure by David Wilkie, 1828

The Guerrilla’s

Departure,

painted in 1828, shows a Carmelite monk offering a guerrilla a light for his

cigar. Tobacco smoking was ubiquitous, thanks to the Spanish colonies in Latin

America, and Wilkie’s depiction of an ordinary working man

smoking a cigar must have startled people back home. And was Wilkie, a son

of the manse, also hinting at Roman Catholic intrigue with the monk offering the

guerrilla a light? The church towers up behind them, and a ragged boy sits on

the ground looking up at the scene. A laden donkey waits behind the man.

The

Guerrilla’s Return by David Wilkie, 1828

The

companion picture The Guerrilla’s Return

(1828) shows the returning guerrilla. He arrives ragged and wounded, his left

arm heavily bandaged, slouching on his exhausted donkey, his gun pointing

downwards in a gesture of defeat. There is no church involvement here; this is

personal. A young woman wearing a mantilla, perhaps his wife or sweetheart, holds

up both hands in distress. Behind him we can just glimpse a man who has,

perhaps, helped the guerrilla get home safely. In the front right of the canvas

a kneeling girl looks up.

The

Defence of Saragossa, by David Wilkie, 1828

Wilkie’s

most famous picture The Defence of

Saragossa (1828) takes as its subject the true story of Agustina Zaragoza, ‘the Maid of Saragossa’. In 1808, the

French besieged Saragossa, a city which had not been attacked for four hundred

and fifty years. The local guerrilla leader, Palafox, and the priest Boggiero, another hero of the resistance, seen conferring at the back, have managed to aim a gun at the French. They are ill-equipped and the ramparts are crumbling. How can they hold off the French with

a few ancient cannons? They are heavily outnumbered.

Turret on the ramparts of Ciudad Rodrigo

Behind the cannon, slumped on the floor, is the dying gunner Zaragoza. His wife,

the twenty-two-year-old Agustina, has seen the French bayonets wreaking havoc on the defenders who are losing heart. Heroically, she runs forward, seizes a match and fires the gun at the French at point

blank range, mowing them down. Inspired by her bravery, the fleeing Spanish

rallied to her defence and, together, they beat off the French – at least for a

while.

The ramparts of Santa Lucia.

Wilkie’s

picture of this stirring event is a highly-dramatic one. The cannon is pushed

up against the ramparts by four straining men. Agustina, in a swirl of white

and pink drapery, holds the lighted taper aloft, ready to fire the cannon.

Behind her, pressed against the ruined city wall, Palafox talks to Boggiero.

Agustina's

story quickly spread. Byron depicts her in the first canto of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Here, she is inflamed by

the sight of her lover mown down by the French.

Her lover sinks—she sheds no ill-timed

tear;

Her chief is slain—she fills his fatal

post;

Her fellows flee—she checks their base

career;

The foe retires—she heads the sallying

host:

Who can appease like her a lover's ghost?

The French, as Byron

puts it, are: ‘Foiled by a woman's hand, before a battered wall.’ This extract comes from Canto 1, published in 1812 while the Peninsular War still raged.

After her heroism at Saragossa,

Agustina became a rebel with the guerrilleros helping to harass the French

and it's good to know that she lived to a ripe old age. Interestingly, Byron actually met Agustina some years after he wrote Childe

Harold.

Bridge over the River Coa, she scene of

fierce fighting

Many of us who

write Regencies have sent our characters to the killing fields of the

Peninsular War. Indeed, I’ve done so myself. So I thought you might enjoy a

glimpse of a different take on the subject with David Wilkie’s vivid paintings.

If you’d like to

see the paintings for yourself, they in the Scottish

Artists 1750-1900: from Caledonia to the Continent exhibition at The Queen’s

Gallery until 9 October, 2016

Other photos

by Elizabeth Hawksley

Elizabeth

Hawksley